This Article was originally published by Khaled Beydoun in the Harvard Law Review. The preface is featured below. Click here to read the full Article.

“My only consolation is that periods of colonization pass, that nations sleep only for a time, and that peoples remain.”

— Aimé Césaire

Journalist: The law’s often inconvenient, Colonel.

Colonel Mathieu: And those who explode bombs in public places, do they respect the law perhaps?

— The Battle of Algiers

Nearly 8 months of genocide in Gaza has marked a sinister new stage of history. Which, with no end in sight, obliges us to look back at revolutionary history.

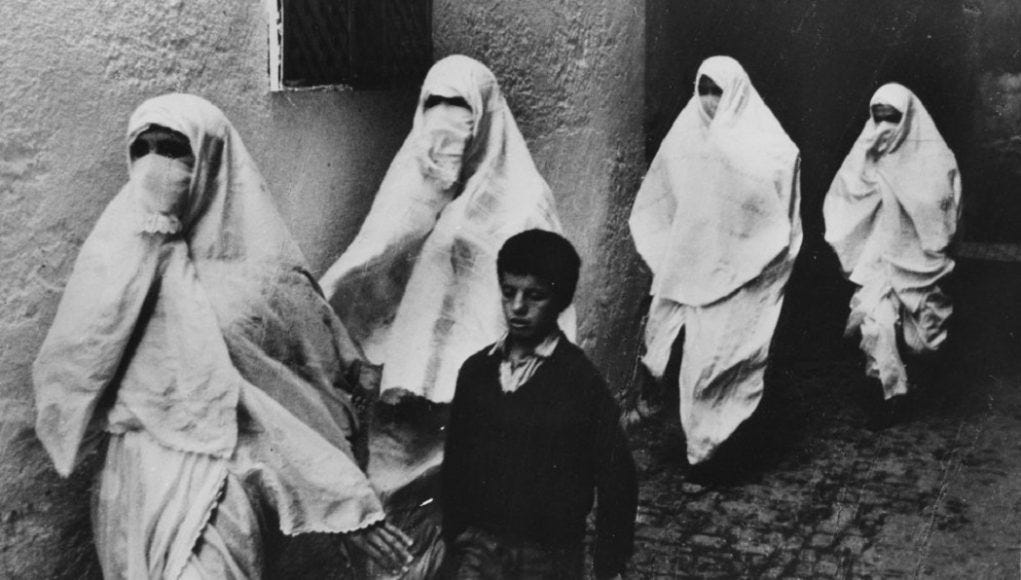

The landmark film, The Battle of Algiers, brought the stunning drama of the Algerian Revolution to screens everywhere. From the winding walkways of the Casbah to the legions of foreign soldiers whirling through them, the film captured the color of imperial horror marked by 132 years of French occupation.

On the silver screen, the world finally saw and understood the Algerians for who they were: a people fighting for their independence with everything they had. Through the director’s subaltern lens, the film exposed the unhinged “barbarism” that loomed underneath the pristine uniform of “civilization” adorned and advanced by the colonial French. The roles of the “terrorist” and “freedom fighter” were cinematically retold, reversing the weight of law and its imprint on colonial history. As the director Gillo Pontecorvo showed and Jean-Paul Sartre wrote: “When despair drove [the Algerians] to revolt, these subhumans either had to perish or assert their humanity against us: they rejected all our values, our culture, our supposed superiority.”

The film, nearly six decades beyond its making, remains revolutionary theatre. It masterfully recreates the asymmetrical battle between the indigenous Algerians, most powerfully the women, who rooted anything and everything from the loins of the land they loved so much to survive the French. Only that brand of love, indigenous love, could scale odds stacked so heavily against them. They faced the limitless legions of colonial soldiers brandishing the most modern weaponry, and the blow of imperial laws crafted to steal rightful claim of soil that sheltered their ancestors and nourished their fight.

As The Battle of Algiers made naked, the law is often the colonizer’s first front. Through word, law strips the natural claim of self-governance deriving from indigeneity, then swiftly unravels the humanity of those resisting with their bodies and being. Law enables the colonial power and his foot soldiers to carry the fight within the most intimate quarters of the natives’ homes. And then, law labels the righteous resistance against it as “terrorism.” The charge of terrorism, per its modern “War on Terror” deployment and earlier use, is crafted powerfully along racial lines, as illustrated by the kindred realities unfolding in the Casbah then, and in accosted squares of Kyiv today.

Law converts that very absurdity — that a foreign force holds possessory rights over a native’s home — into the manmade fiat of manifest destiny. Brutal soldiers invoked this legal authority crafted by foreign men in distant capitals and cruelly imposed it on natives as their new fate. This is the law’s cardinal function in settler colonial states like America and imperial experiments such as Algeria — to delegitimize self-determination and dehumanize those who resist.

“The rule of law?” Aimé Césaire asks rhetorically: “I look around and wherever there are colonizers and colonized face to face, I see force, brutality, cruelty, sadism, conflict . . . .” Law, in this sense, is an imperial instrument, molded and maneuvered to advance the interests of those that hold power over it and power over the machinery that translates authoritative law into ominous violence. Law is most lethal when it envisions its targets as objects of conquest rather than subjects of patronage.

The discourse between the journalist in The Battle of Algiers and Lieutenant Colonel Philippe Mathieu brings this imperial expedience of law, or convenience, to vivid display. Mathieu is the cinematic embodiment of the steely French entitlement driving its colonial obsession of Algeria. With regard to Ukraine, the French stand as a telling archetype for the arrogant authoritarianism of President Vladimir Putin, whose obsession with power is wed to a kindred nostalgia of Soviet regional and global hegemony. This discourse about law and power, imperialism and indigeneity is built upon an undergirding epistemic about freedom fighters and terrorists — a timeless dialectic that screams from the screens as if from The Battle of Algiers.

Political reality, after all, inspires the best cinema. In a world marred by two decades of a global War on Terror, racial reckoning, and cold wars of the past thawing to restore bygone geopolitical rivalries, modern reality is as gripping as fiction. Terrorism has taken on a pointed racial and religious form. Muslims, transnationally, have been “raced” as terrorists as a consequence of this American-led crusade. Their faith is conflated with extremism and their portrayal in American media is constructed based on that conflation.

More than legitimizing this indictment, global War on Terror law and propaganda have spearheaded its construction. In turn, they unravel the humanity of Muslims in favor of a political visage that enables policing and prosecution in America and military persecution and mass punishment abroad. This occurs even in lands where Muslims — like the Algerian women and men in Gilo Pontecorvo’s classic film — are striving for self-determination against modern imperial actors. Seeing them as terrorists facilitates the unseeing of them for what they rightfully are: freedom fighters struggling for the very dignity that Ukrainians, taking arms in the midst of impending conquest, clench onto in the face of imposing Russian aggression.

The force of the imperial law, that simultaneously strips the land from its rightful holders and constructs them as inferior or inhuman, is most potent when driven by a “racialized” frame. Postcolonial thinkers of eras past, most trenchantly Césaire, Frantz Fanon, and Edward Said, revealed how the accompanying hand of racism expedited the plunder of nonwhite peoples.

Today, critical race theorists emphatically and incessantly affirm racism’s centrality to law, against the political and legal tidal wave that seeks to disfigure and discredit it. There is perhaps no theatre of law where the centrality of race is on fuller display than the War on Terror, where the unabashed demonization of Muslims remains politically palatable and culturally pervasive. Islamophobia stands, almost singularly, as a final bastion of acceptable bigotry. This is especially apparent in the United States, and a globalized world remade through a War on Terror lens over the last twenty-one years.

The color of freedom and terror is intimately tethered to the world order remade by the War on Terror. Muslims are “presumptive terrorists,” a charge levied on account of race, religion, and realpolitik, even when acting as freedom fighters. A distant, yet kindred campaign for self-determination reinforced the power of this indictment, with a racial design as its marrow. It took form in Europe, beginning on February 24, 2022, when Russian missiles “rained down on the Ukraine,” foreshadowing the thunderous military storm seeking to restore reign over the former Soviet colony.

The formidable Russian army rushing in from the east was rightfully and universally branded “imperialist,” while Ukrainians, from the highest rungs of political office to the deepest roots of lay society, were globally celebrated as “freedom fighters.” Ukrainians embodied the indigenous fight of Algerians then, or Yemenis and Kashmiris today, against a global military power intent on crushing their hearts, homes, and everything they love beyond and in between.

Unlike the accusations leveled at Ukrainians’ Muslim counterparts striving for self-determination, the Russian indictments of “terror” lacked the dehumanizing hand of race and racism. Rather, the indictments were countered and quelled by their targets’ lurid whiteness, and Ukrainians were celebrated as freedom fighters on the basis of their whiteness coupled with Western opposition to the Russian invasion. It took little for Ukrainians, whose faces monopolized the news headlines and timeline feeds, to become universal darlings and irrefutable victims.

The Western world flanked alongside President Volodymyr Zelensky and the Ukrainians’ archetypal whiteness twice mooted Putin’s levied charges of terrorism from Moscow. Ukraine is ninety-nine percent white, and politicians and media outlets all over the world hailed its people fighting for resistance and pushed from Ukraine as refugees. As Césaire wrote during the thick of the postcolonial era of the 1950s: “Europe has this capacity for raising up heroic saviors at the most critical moments.” This heroism is monopolized by whiteness, embodied decades later by blonde-haired and blue-eyed Ukrainians at the “critical moment” of NATO expansionism clashing with Russian imperialism.

Race, far from a fringe actor, is central to the dramatic play unfolding within Ukraine and beyond it. By interrogating the centrality of race in the dialectic of freedom and terrorists, this Essay examines how the realpolitik driving imperial law and its accompanying discourses is powerfully abetted by racial difference, and the indelible resonance of whiteness when it occupies the role of freedom fighter.

The War in Ukraine, distinctly unfolding alongside similar campaigns in the “Middle East” and Muslim-majority contexts, is a powerful theatre illustrating this dissonance; such dissonance colors the framing of “nonwhite” Muslims vying for self-determination as terrorists and white Ukrainians, engaged in the very acts of resistance, as freedom fighters.

This racial interplay saturates media discourses, scholarly literatures, and as new wars converge with preexisting crusades, across screens drilled to walls and smaller ones held in our palms.

Through its examination of new war, this Essay builds on foundational literatures interrogating the construction of racialized threat and colonial victimhood. In doing so, it interrogates how the War on Terror creations of terror threaten to extend beyond American borders geographic and political, converging with a globalized formation of whiteness that extends presumptions of innocence and valor to those who hold it.

Echoing the formative critical race baseline that racial construction is not separate from political interest, this Essay stands as the first to examine this very discourse within one of the most consequential wars of this era — centered as such because the white identities of its lead actors align with the geopolitical stakes of the conflict.

Click here to read the full article.

Khaled A. Beydoun is a law professor and author. He publishes his daily insights on his socials at @khaledbeydoun.

Always look forward to your take and vision of social injustice and knowledgeable facts!

The film "The Battle of Algiers" was shown by the founder and director of The French Cinematheque on May 1, 1968, and it was there, at the Place de Trocadero in the 16th arrondissement in Paris that the student riots began after that screening.